Can You Moonlight as a Winemaker?

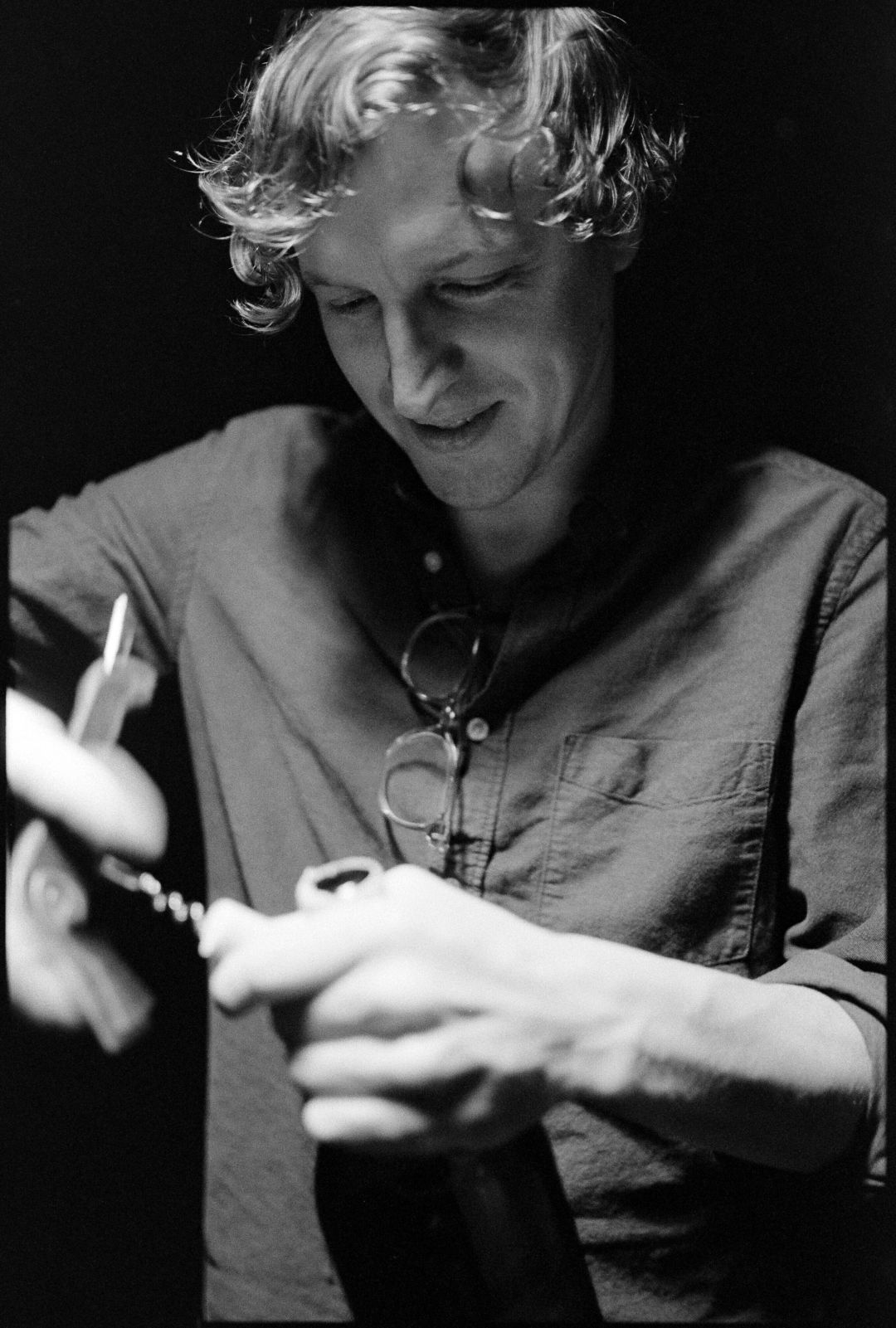

Tyler Magyar's side hustle making wine has grown into a full-fledged business.

Image:Courtesy Tyler Magyar

“Can you do it on top of your day job?” That’s the perennial question Tyler Magyar asks himself when deciding how many grapes to order for next year’s harvest. Magyar, who owns the local natural wine producerMonument(who’s rosé “Jenny” came out on the top ofPortland Monthly’sreview of 10 local Oregon rosés) also works full-time as the wine buyer for the Pearl District international grocerWorld Foods.

In today’s market of side-hustles, the gig economy, and DIY-ing . . . everything, wine might seem too gatekept an industry to break into as a passion project. You need the funds—the generational wealth; wine is expensive and sophisticated, made by people in drapey white linen with loafers and perpetually wet hair, no?

“Well, I am wearing a blue linen shirt today,” Magyar quips.

Magyar didn’t grow up in a Burgundian vineyard or on an estate in the Napa Valley but on the Jersey Shore, where it seemed like half the town took the train to their jobs on Wall Street. “I grew up in shops,” he says. Through watching his father, a chocolatier, work all night to make bunnies on the eve of Easter,Magyar learned how much joy there was in sharing a passion with patrons. (“It was to make money, sure, but helovedit.”)

Culturally, wine’s never had the social bar to entry for Magyar that some place on it; instead, he sees it simply as a specialty product, like his dad’s chocolates or boutique candles or bread from a favorite bakery. “If your point of entry is: ‘this guy really loves something—he carved a space for a thing,’ you get to forego a little bit of the pretense,” he says.

As a teenager, he translated the sentiment to the world he lusted after: record stores and video shops, envying the unparalleled clout of twenty-somethings that embodied magazines likeSpinandNME. He longed to breach an insular community of obsessive—to be the one recommending Fugazi. “High Fidelity, the video store . . . all of that,” he says. (He'd like to be John Cusack, but says he’s probably more Jack Black.)

Friends describe Magyar as “an eccentric.” “Tyler’s maybe one of the most passionate people I know,” says Lisa Nguyen, who manages the natural wine bottle shopArdorin Southeast Portland. She says he’s like a theater geek—extremelyearnest.

Before making wine, most of Magyar’s time was devoted to “soaking up knowledge,” to becoming some version of the record store employee. He moved to New York City after high school to study “Arts and Contexts” at The New School, while working in the cellar of a wine store, stealing underaged sips where he could. “The college major was: be interesting at a dinner party,” he says. A year-long internship atFood and Winefollowed school, but that job trajectory ended with the financial crisis in 2008.

On a whim, he took a job as a nanny in Paris and “hid” from New York City living costs for a few years, all the while becoming acquainted with the casual wine culture in France.

非盟对逗留,后回到纽约,回来in wine shops, Magyar started to see accessibly priced Oregon wines from producers likeFausse PisteandBow & Arrow. “Labels that shouted something different than ‘I’m fancy,’ or ‘I’m affordable’; they had personality and grit,” he says. It was here that he first saw wine through the lens of professional appreciator: "They reminded me of wines in France that were sold by the equivalent of a punk rock salesperson at the record store, that movie nerd at Blockbuster, my dad making chocolates. . . .”

Scott Frank, the winemaker behind Bow & Arrow, now a friend of Magyar’s, says they share this language of metaphor. “It's just so easy; if music shaped your life when you were young—informed how you dressed and who you hung out with and was the emotional core of your teenage existence. . . . I know exactly what he means when he says the ‘Fugazi of wine.’ That’s all freaking . . . that’s all killer no filler, you know?”

Regardless of his feelings about who was allowed to enjoy wine—to drink it and sell it and talk about it—when a friend mentioned the concept of making wine to Magyar, he was full of culturally-imposed doubts: “I don’t have the money; I’m not that serious; I can’t jump over that barrier to entry; and I’m not a white table cloth guy!”

His first harvest was with Andy Young who owns The Marigny winery in theWillamette Valley.Almost instantaneously, the rush of the process took hold of him. Young had moved into the city for the season to make wine in a space inSellwood.“What was a light agreement of ‘one to two days a week . . . or something like that’ turned into him helping me every day through the entire 2017 harvest,” says Young.Magyar would leave his day job in the evenings, bike 45 minutes down the Springwater Corridor to the winery, make wine all night, then bike back to the city with a corkscrew between his fingers (“in case someone tried to attack me”), nap under his boss’s desk, and repeat.

The next year, Young lent him a small space to experiment with a batch of wine. His third year making wine, 2018, was Monument’s inaugural commercial production. The fever-dream feeling compounded: every year his production grew and all of the sudden,withoutleaving his day job, Magyar had a winery.

“And at that point, you cash out the 401k from your last job and everything becomes a little more real . . . and then harvest again rolls around,” he says. Now, the days of working around the clock and dangerous midnight bike commutes are behind him, sort of. His operation still has its quirks. As a,négociant, or winemaker who buys grapes in lieu of growing them, Magyar’s system involves rented Penske trucks and tents, sleeping on vineyards and helping with the 10–12tonharvest. Which of course, is only the beginning of the demanding process of preparing and crushing the grapes.

“My space looks like a warehouse because it is a warehouse,” says Magyar. He works out of the same space in Sellwood that Young invited him into years ago (“between the Goodwill bins and the Acropolis strip club”). He shares the warehouse, a forklift, and some grape processing equipment with local wineries Flat Brim and Fausse Piste—the same label that sparked his imagination from across the country a decade ago. He jokes about the “native yeasts” of the space, the terroir of the storage facility they took over from a property management company, where the belongings of evicted tenants were once held.

A selection of Magyar's wines.

Image:Courtesy Tyler Magyar

纪念碑专门生产天然葡萄酒,一个怪兽m that’s rich in connotations, but simply means they’re made without additional yeast to jump-start fermentation. Instead, the crushed, pesticide-free grapes ferment via “wild” yeasts—what’s naturally in the air. Magyar calls them “the goblins.” Sulfur is the only addition, which helps stabilize the wine as it travels and ages.

Everything orange and skin contact is no doubt enjoying a vogue of trendy ignorance (“bring us whatever’s funkiest!”), but Magyar is most interested in the politics of the process, valuing the safety it promises the farmers he works with. The goal of Monument is to make approachable natural wines, “wines that are pleasant enough for your mother-in-law to enjoy. But with the aesthetic and feel, the realness and aliveness of those wines that I’ve sold for so long,” says Magyar.

Monument’s 2021 vintage, 750 cases of wine made from 20,000 pounds of fruit, cost Magyar half the salary of his day job to produce.A small-ish production relative to other producers, but multiple flatbed trucks of grapes dwarf most people's hobby closets. (Bow & Arrow, by contrast, produces just over 5,000 cases per season, the threshold of what Frank says allows him to still have his hands in things.) In spite of limited numbers, Magyar’s wines are distributed across Oregon, in New York, Chicago, Washington DC, and as far as South Korea.

Scale of course, is a necessity of running a business. The hustle of punching your way into an industry is too. But both Frank and Young are most taken by the quality of Magyar’s wines. “The good ones get their personality into that bottle somehow. I was always looking for Tyler’s exuberance and his personality to find a way into the wine. And they did,” says Frank.

“最严重的是捕捉人民imagination, creating something that’s just different enough to stand on its own,” adds Young.

Magyar’s not sure if he’ll everonlymake wine, but he does struggle to keep straight which of his careers he’s moonlighting in. “And then I have this side job,” he says, laughing beforehalfheartedly correcting himself: “It’s not aside job, it’s acareerI have.”